I received way more feedback to my post explaining what exactly a product manager does than I had anticipated—a huge thank you to everyone who took the time to share thoughts, feedback and questions.

And speaking of questions, there were lots of good ones, the majority of which touched on a few recurring themes. I had originally intended to post one all encompassing follow-up in which I addressed each of them, but, given how long it’s taken me to get through just one answer, I decided to go ahead and publish my responses piecemeal. Apologies for the glacial pace of my replies!

Before diving into my first piece of follow-up, however, I wanted to share two film recommendations as we head into the weekend. The first, which is still in theaters, is called BALLET 422 and it “takes us backstage at the New York City Ballet as Justin Peck, a young up-and-coming choreographer, crafts a new work.”

I’ve never been a particularly big fan of ballet, but I found this film exhilarating, both in its depiction of the remarkable artistry and athleticism of the dancers, and in the way it captures the process of creation: its loneliness, its conflicts, its demands for partnership and its glorious moments of shared discovery. I think anyone working in product management will see parallels with their world and may come away with learnings that can be applied to their day jobs, particularly around the ability to balance individual vision and group collaboration.

If you’re a product manager in search of filmic inspiration this weekend, I’d strongly suggest BALLET 422, which is in theaters now, and Steve Jobs: The Lost Interview, which is available on Netflix streaming. Images from BALLET 422 (left) and Steve Jobs: The Lost Interview (right).

The second film is Steve Jobs: The Lost Interview. Though it hit theaters in the wake of Steve Jobs’ death in late 2011, the interview in question actually took place in 1996. The interviewer, Robert X. Cringely, captures his subject at a unique moment in time, when Jobs—who was never one for retrospection—was willing to talk candidly about his history at Apple, and the formative experiences that shaped his views on product creation, technology and leadership. What’s remarkable, given how long ago the interview took place, is how timely it remains in content, if not in video quality. Unfortunately, Steve Jobs: The Lost Interview is no longer available for purchase via any of the leading digital media services, but it is available for streaming on Netflix [Note: Sadly, The Lost Interview is no longer available on Netflix].

Okay, so on to follow-up, part one...

This is a really interesting question from Ryan Singer at Basecamp, formerly known as 37signals (my old stomping grounds!).

For people who’ve only ever worked at start-ups or very small companies, the answer may seem self-evident: If you need resources you ask the founder, and he or she will give you a yea or nay right then and there. But for anyone who’s worked at a larger firm—whether that firm deals in bits or in bolts—Ryan’s question will no doubt conjure dark memories of the Rube Goldberg-esque organizational apparatus nestled at the heart of most megacorps.

I have plenty of stories I could share about navigating that maze, but that’s another topic for another time. Getting back to Ryan’s question, I’ll start with the first half: The force that most frequently constrains a product manager—from above or otherwise—is inertia. This is because most individuals dislike change and, barring a strong opposing force from above, this individual antipathy seeps into a corporation’s broader culture, smothering any inclination towards innovation.

Even in companies with a history of risk-taking, it can be incredibly difficult to get a new idea over the top. That’s because, while many people love to talk about innovation and taking chances, very few have the courage to act when that action might jeopardize their personal financial security or career prospects. It’s also true that there are simply a lot of fucking intellectually lazy people in the world who can’t be bothered to learn anything new.

Sadly, our culture gives these people plenty of cover: Expressions like “Don’t rock the boat,” and “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,” and “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” cloak inaction under a veneer of wisdom. But these bromides no longer hold water—I never thought I’d quote Mark Zuckerberg, but he’s spoken powerfully on this topic and, critically, has shown a willingness to back up his words with actions:

“The biggest risk is not taking any risk... In a world that’s changing really quickly, the only strategy that is guaranteed to fail is not taking risks.”

It’s important to emphasize that I’m not suggesting companies take risks willy-nilly. As someone who co-managed a micro start-up in 37signals, I know that everything a company does comes with very real costs in time, attention and capital. And, as someone who’s managed multi-million unit product lines at Nike, I’m well aware that product leaders must thoroughly consider the pros and cons of any potential opportunity before acting. But too many companies today are in perpetual harvest mode, seeking to eek out every last drop of value from existing products and processes before investing in better, higher value solutions.

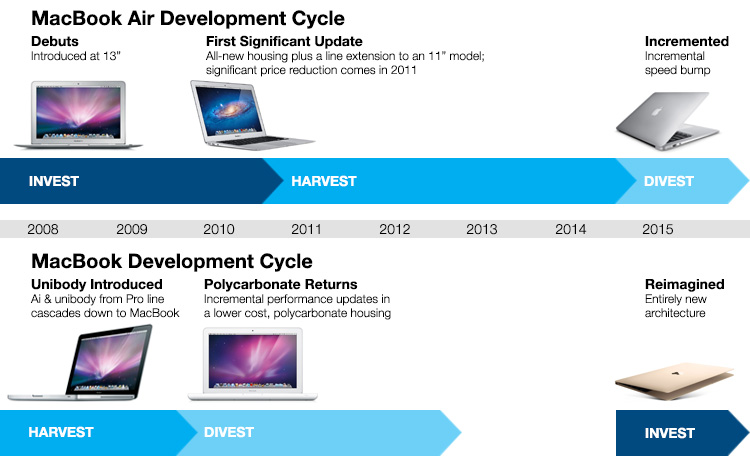

Spend any time studying Apple’s product cycles and it quickly becomes evident that the company maintains a highly structured approach to its cadence of evolutionary and revolutionary updates. The strong sales of established lines enables investment in new, high-risk products that start at low volumes, but grow to subsume previously established franchises. Their offset invest/harvest/divest cadence also helps to mitigate any downside impacts associated with weaker-than-anticipated adoption within any one product line. This willingness to invest in new concepts and, just as importantly, divest of older ones, is a critical contributor to Apple’s continued success in the hyper-competitive consumer electronics space.

The problem with this seemingly prudent approach is that, by the time they’re done sucking blood from their precious stones, the marketplace has moved on and left these risk averse companies in the dust. Just ask the folks at Kodak or Blockbuster how well a strategy of perpetual harvest (the corporate euphemism for this is, “we’re focusing on our core businesses”) worked out for them. And yet, though cautionary tales illustrating the risk of not taking risks abound, sticking with the status quo remains the default mode within most organizations.

This may lead you to ask a new question, namely, how can I convince my company to be more open to risk? This has become a popular topic amongst business journalists and management consultants in recent years, with leading players like Accenture, The Economist, Harvard Business Review and McKinsey devoting much brainpower to the discovery of an answer. I know this is going to sound defeatist, but, in my experience, if a company’s leadership doesn’t already have a healthy appetite for risk, no amount of kicking, screaming or reasoned argument from below will be sufficient to effect change. As such, my advice to those who feel consistently hamstrung by organizational inertia is to find a new job at a company that’s shown a willingness to take smart chances or take the plunge and start a company of your own.

Now for the second part of Ryan’s question: How do products get resources? The specifics will vary from company to company, but the CliffsNotes version is pretty straightforward: Make a compelling case for your product.

In some companies this will entail lots of quantitative research, such as data on historical sales of related products, sales or usage trends across your broader market or important behavioral trends. For example, during my time in the ad world, my team successfully persuaded a large client to pursue a big-budget second-screen marketing campaign based in large part on behavioral research showing that second-screen viewing was exploding in popularity amongst their target audience. This supporting data gave our client the confidence to fund what was initially viewed as a risky proposition, and their return was an innovative campaign that delivered engagement levels far beyond industry norms.

Oftentimes, however, you’ll need a blend of facts and feelings to get a new product concept funded. For instance, at Nike, a pearl of wisdom from Phil Knight that anyone involved in product creation lives by is: “Always listen to the voice of the athlete.” This maxim is part of the bedrock of the company’s culture, so qualitative feedback from athletes (i.e. customers) holds tremendous sway at the Swoosh—much more so than it would at a more analytically driven company, such as Google. But, that being said, in order to get the highly unconventional Nike LunarGlide+ running shoe concept through the company’s organizational matrix, I had to buttress the positive feedback we received from early focus groups and wear tests with copious data on marketplace trends, as well as findings from our Sport Research Lab, which showed that the shoe offered quantitatively unique performance benefits.

You may be surprised to learn that there was no product manager’s handbook at Nike that walked me through the steps to success. Perhaps at some companies there is, but my experience tells me that it wouldn’t have been much use anyway, because I’ve yet to see two product creation scenarios play out in precisely the same way. I think this ability to empathize with and address the needs, questions and doubts of internal stakeholders is as crucial to the success of a product manager as is his or her ability to empathize with and address the needs of prospective customers. Because, if you can’t do the former, you’ll never get the opportunity to deliver on the latter.

I hope this helps and, as ever, let’s keep the conversation going on Twitter @edotkim.